Collection of ideas

Ni ĉiuj konscias, ke ni apartenas al unu granda familio…

L. L. Zamenhof

We are all aware that we belong to one big family...

Zamenhof considered Esperanto as just one contribution towards the larger project of achieving world peace. Hee articulated this larger project, naming it Hilelism and later Homaranismo (‘Humanitarianism’). The project’s goals were to unify humanity by creating a new neutral culture whose members would be divided geographically and politically, but not by their language or religion.

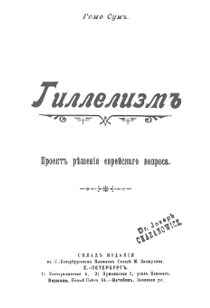

As a younger man, Zamenhof had been a proponent of Zionism, but went on to renounce Zionism in 1886. He nonetheless remained conscious of his Jewish identity, and it was something which he cared about. One of the reasons for this is that the fate of the Jewish people in Eastern Europe seemed more and more hopeless at the time. It was in this context that Zamenhof first proposed his Hilelism project in April 1901 as a solution to the Jewish Question. In short the ideas of Hilelism are captured in this sentence, "Treat others as you would like to be treated yourself". To elaborate a little bit more, that everyone should consider themselves as part of the whole, not as separate from the rest of the community or of humanity. Whilst the sentiments of Zamenhof’s philosophy are universal, it was widely received as ‘just another “-ism”’, and did not find much support. In fact it was widely criticised for excessive idealism.

When faced with opposition to Hilelism, Zamenhof momentarily stopped speaking about his ideology. An international language could, he believed, solve many problems: it could empower people to effectively communicate and to clarify their opinions. For some time, he focused his energies on this. However, several years later, in the context of the Russo-Japanese war from 1904 and the 1905 Russian Revolution, he revived the project. These events strengthened Zamenhof’s belief that an international language could only be a means to an end - and that a language could not be an end in itself. The imperialist war and the socialist revolution prompted Zamenhof to take the next step towards attaining peace among all people. That is, he returned to the idea of Hilelism, albeit on the understanding that Hilelism required great reform. And so he opened by Hilelism from a project specifically for Jews, to a project which would welcome all.

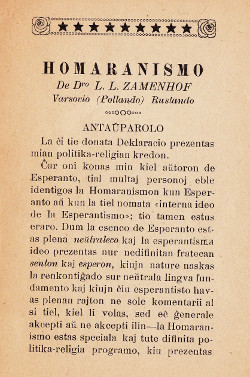

In January "Ruslanda Esperantisto" (1906) he anonymously unveiled his doctrine under the title "Dogmas of Hilelism" with parallel Russian and Esperanto texts. The name referenced Hillel the Elder, a Jewish religious leader who had lived slightly before the time of Christ. Zamenhof realised that this name was very Jewish, and thus might put people off. He also realised that the foreword was too Russocentic. And so, a brochure with the name "Homaranismo" was released in March in Saint Petersburg. The foreword of this second edition acknowledged that while Hilelism really only concerned Jewish people, that Homaranismo concerned everybody. The text contained new teaching about how to conduct relationships in the home, nationally, and internationally. The belief system was summarised in 22 paragraphs. Intellectually speaking, the roots of Zionism lie in the Romanticist paradigm. That is, Zionism desired that the label Jew would be elevated to a national and even state status. Zionism sought to attain for the label Jew, the same status held by terms like Frenchman, German and Russian. Zamenhof went further than this, arguing that we (humans) should consider ourselves not as belonging merely to any particular religion, language group, or nation, but simply as belonging to humanity.

Here are the first four dogmas, the most principal and general:

- I am a human, and the only ideals for me are are human ideals. I use the word 'human' in the widest sense of the word. To me, ideals which are only concerned with one specific group or nation are nothing more than egotistical tribalisms which, consciously or otherwise, bear hatred towards others. Sooner or later, these ‘ideals’ must be done away with. I must, according to my abilities, do my bit in consigning them to the dustbin of history as quickly as possible.

- All nations are equal. If I judge somebody, that should only be on account of their value as an individual and their deeds, and should not be influenced by any prejudices or opinions about the individual's ethnicity. All kinds of abuse and persecution relating to a person’s nationality, language or creed are acts of sheer barbarism.

- In my opinion no country should belong specifically to any particular nation or group. I seek to uphold the equal treatment of all peoples, and to protect people from imperialism. Therefore, I believe that each country must belong to all of the people who live there, regardless of their language or religion. The interests of the state are often conflated with the interests of specific nations, languages and religions. To me, this is an anachronism which has been tragically leftover from barbaric times when only might was right. We must move forward in a more positive direction.

- In family life, everybody has the indisputable, complete and natural right to speak whichever language or dialect which they may desire. Similarly, I advocate absolute religious freedom, within family life. However, when communicating with people from different backgrounds, it is best whenever possible that a neutral language is used, and a neutral non-sectarian manner of moral behaviour is adhered to. It is barbaric to try to impose your language or religion onto other people.

Zamenhof’s original plan had been to launch the Homaranismo project at the second Universal Congress in Geneva, 1906. But he was convinced by a friend to delete much of his speech, specifically the part where he would have state that the purpose of Esperanto is to enable Homaranismo. Zamenhof came to realise that despite the euphoric atmosphere during the first Universal Congress in Boulogne, that Esperantists ultimately were not prepared to accept Homaranismo or the mission of ‘reuniting humanity’. Even his closest Esperantist acquaintances strived to persuade him not to link Esperanto with a religious doctrine. In this context, Zamenhof refrained from any public mention of Homaranismo. However now and again his passion for his beliefs overflowed, and he could not entirely hide them, and so he spoke in a rather vague way about what he called Esperanto’s ‘internal idea’. In 1912 Zamenhof defined the internal idea like this:

It is not necessary that every Esperantist becomes compelled by the internal idea of Esperanto. Nonetheless, the internal idea fully governs Esperanto congresses, and it must continue to do so. But what is the internal idea? That the fundamental linguistic neutrality of Esperanto can remove the cultural and language barriers between people and make Esperantists gradually recognise the humanity of people from other backgrounds, even the brother and sisterhood of all peoples. This will affect different people in different ways, an almost infinitely diverse variety of ways. An individual’s highly personalised response to the internal idea should not be confused with the internal idea itself.

[Translator’s note: for example, somebody who belongs to a prestigious group in society may have a humbling experience, whereas somebody from background which is of lower status may find the experience deeply empowering].

As someone who was born and educated in the multi-ethnic Russian empire, Zamenhof was unaware of the level of linguistic heterogeneity in Germany, France and other western-European countries. Similarly, he did not fully realise that religion had lost its cardinal role in society. He therefore overly fixated upon language and religion, and overlooked how political, economic, and psychological factors also must be addressed to achieve the type of society which he desired. He held that the root of division between nations cannot be attributed to the political, economic, geographical or demographic situations. This belief of Zamenhof is evident not from his words, but more from his omissions. Rather, to Zamenhof, division in society could mostly be attributed to misunderstandings stemming from the multi-ethnic, multi-religious situation, and so the "inter-racial division and hate will completely disappear for the humankind only then, when all of humanity will have one language and one religion".

As Esperanto had successfully demonstrated its ability to eradicate linguistic division. To Zamenhof, what was now required was a solution to the matter of religious division. In 1913 he released his proposal to organise a congress for a neutral humanistic religion in Paris, as a sister event to the 10th Universal Congress of Esperanto, 1914, which was ultimately cancelled due to the war. Zamenhof’s proposals for a religious congress were quite unusual. He did not want to speak to people who believed that their religion was the sole god-given belief system. Rather, Zamenhof wanted to speak to free thinkers, people who had left the religion of their forefathers. His Declaration had four theses, a maximum of three of these can be considered to follow the religious dogma of Homaranismo, and the fourth related purely to organisation.

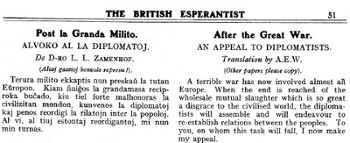

In late 1914 Zamenhof wrote an open letter to political diplomats titled ‘After the Great War’. He sent it to several the editors of several Esperanto journals for publication both in Esperanto and for translation and wider distribution in national languages. He correctly predicted that diplomats would redraw the political map of Europe in the post-war period. The therefore proposed the establishment of a United States of Europe. He understood that his vision would not come true, but felt that the argument should be made nonetheless. He also felt that he really could exert some influence, and inspire the political leaders of Europe to guarantee that ‘each country belongs to all of its sons and daughters equally, morally and in a material sense’.

Zamenhof incessantly worked on his Homaranismo project until he eventually finished writing the final version just two months before his death. The new foreword of this final updated version of the text made a clear distinction between Esperanto and Homaranismo. The doctrine was now stated in competely new terms:

Under the auspices of the ‘Homaranismo’ project, I want to talk about; how we must strive to achieve Humanity; about the abolition of sectarian injustices and hatred between nations; about a more righteous way of life, which could ultimately bring about spiritual unification of all humanity. I am not discussing theory, I am discussing practice!

Zamenhof really had changed his tune in this final version of the text. Previously, in the first edition, he had described the aim of Homaranismo as seeking to bring about the melting together of nations into an international neutral civilisation. Now, in the final edition, the aim is described as achieving the ‘spiritual unification of all humanity’. That is, although the religious tone has perhaps intensified, Zamenhof is also more willing to accept that national cultures should not be supplanted, but supplemented.".

With each version of the text which was released (Hilelismo 1906, Homaranismo 1906, Homaranismo 1913, Homaranismo 1917), Zamenhof gave increasingly less attention to the language problem. In the 1906 editions, Homaranismo is presented as closely related to the Esperanto project. There was no mention of Esperanto whatsoever in the 1913 and 1917 editions. The 1913 does mention a neutral language for humanity (without mentioning Esperanto or any other language by name), but this is absent from the 1917 edition.

The 1917 edition effectively targeted itself at an entirely different group of readers. The 1906 edition ("Hilelismo" 1906) specifically addressed the Jewish community who lived in the Tsarist Russian Empire. This was removed from later versions of the text. The early versions were also targeted at people who interested in Esperanto or another international auxillary language. But the 1917 edition removes this requirement from the readership, broadening the target audience, addressing all members of the human family, all around the world. Indeed, Zamenhof intended that the text would be distributed not merely within the Esperanto echo chamber, but distributed widely throughout the world in the most widely understood national languages.

Indeed, the pursuit of humanity, the campaign to end sectarian or racist hatred, and the efforts to bring about the spiritual unification of all people; these are much broader topics than linguistic/religious unity alone. Furthermore, the Golden Rule, ‘treat others as you would like to be treated yourself’, transcends religion; it is truly universal and moral. The translation of this principle (and the principles of Homaranismo more generally) from theory into practice could attract would be a good advertisement for the belief system. This would be able to attract not just to the usual Esperantists and Bible-bashers, but also to all ordinary people who supported progress in society, but who weren’t so interested in languages or religion.

Just a few weeks before he died, Zamenhof started to write his last essay ‘On God and Immortality’. Unfortunately he never had a chance to finish writing the work. This unfinished essay started to outline beliefs which Zamenhof had adopted rather suddenly and which he thought would spark controversy. It was a response to ‘various scientific and philosophical texts which [he] had read and meditated upon’, however due to the unfinished state of the article, we do not know which works he meant.

Zamenhof passed away in 1917. He was passed away by his three childrem, Adam, Zofia and Lidia, each of whom were later murdered by the Nazis in the Holocaust. He was the author of the Esperanto language, a great gift to the world, as well as many translations and timeless ideas which continue to inspire people; people who consider themselves not just members of their own nation or religion, but also members of the human race; people who believe in its unity and diversity.

Sources

- Korĵenkov A. Homarano: La vivo, verkoj kaj ideoj de d-ro Zamenhof, Kaliningrado, Kaunas, 2009

- Privat E. Vivo de Zamenhof , Rikmansworth, 1957

- https://eo.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interna_ideo

- Korĵenkov A. Zamenhof. Biografia skizo, Kaliningrado, Kaunas, 2010

- https://eo.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homaranismo

- https://eo.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hilelismo